“What the hell are you trying to prove?”

My safety glasses are steaming, and sweat is rolling down from my hard plastic helmet. It’s loud as hell in this factory, so I’m not exactly sure what I’m being told.

My shift supervisor just shut my machine down so he could chew my ass. He is pissed, and I am confused.

Am I being scolded for being too productive?

I worked an internship for an automotive parts supplier in Detroit when I was in college. The work was related to my engineering major. I worked with a manager to find more efficient ways to manufacture trunk hinges.

We agonized over design methods that would take even one second off of the manufacturing time on these hinges. We eliminated one component, tested a new material that would require less grease, and moved a rivet slightly, so two were pressed at one time.

The premise of my internship was finding ways to manufacture more parts in an eight-hour shift.

For two months, I generated ideas, tested and ran time trials to squeeze seconds out of the process. As a young kid, I hoped the company would adopt a few ideas and save enough money to justify my three-month stint.

Late in this internship, our business picked up, and we had a shortage of labor. Also, the union was negotiating a contract and rumors were growing of an impending strike.

Our company offered shifts to the office workers to make up for the shortfall. I was a broke college kid and couldn’t raise my hand fast enough. Plus, I was excited to manufacture some of the parts and get a feel for the front line.

Our first shift would be weekend work. On Friday, the volunteers gathered on the factory floor for some quick and dirty training. Our trainer was a shift supervisor who belonged to the union.

He made sure to tell us that 800 parts were the goal for a shift. He let us know about safety, allowable breaks, and sequencing. Then, he would come back to the magic number of 800. He told us it was okay if we came up short. We were only temporary help and shouldn’t push the output past 800 as this would “put quality at risk.”

I found this odd as machines were mainly doing the work. The process was simple. There were 7–8 components that we needed to assemble on a manufacturing pod. We pushed a button, inspected, and discarded parts into a bin before moving on to the next one.

I came in Saturday, ready to save my company from economic ruin, all in one shift. It was time to roll up my sleeves and pull the organization out of our poor fortunes. I listened to “I need a hero” on my way to work.

It’s go time.

I was cautious for the first hour but got into a rhythm and caught fire. I burned through parts and with excellent quality. I took no breaks that morning, and by lunch, I was sweating through my clothes in that hot and humid factory.

Just before lunch, the shift supervisor stopped by. He looked in my finished part bins and immediately shut down my machine. He looked like someone just kicked his dog.

“How many parts did you make?”

“A little over 600.”

The shift wasn’t even halfway over.

He gives me an ass chewing like I was a recruit at military boot camp. He goes on and on about how I could compromise quality.

Reckless.

Irresponsible.

A few “f-bombs.”

I politely ask him to inspect my parts. I am confident he will find that they are of the most exceptional quality. I spent two months working on quality for the company and would never jeopardize it for speed.

He tells me that it doesn’t matter and stomps off.

I was confused. My company is lacking human resources and needs as many parts as possible in the shortest period. On top of that, I just spent the last two months devising new methods that could squeeze a mere 1% more production out of the line.

Now, I am proving that we can do 1,200 parts in one day and I get for it?

One of the older union workers saw this exchange and walked over. He was a great guy that I often chatted with while waiting for my food truck order at lunch.

“Why do you think he’s mad at you?”

“I don’t know; I guess he thinks I can’t maintain quality at this pace?”

“Nah, it’s not about quality. We’re negotiating a new contract. We are asking for more pay to do this job. How do you think it is going to look in the negotiation when a kid from college came in and did 50% more output on his first day?”

“Not good for the union but good for the company.”

He pointed to my shirt, which was soaked with sweat. He then pointed to his shirt which was not.

“You are on your first shift. This is all new and exciting to you. Anyone can keep that pace for one day. I’ve been here for 25 years. Do you think you could keep that pace every single day, six days a week for the next 25 years?”

Of course not.

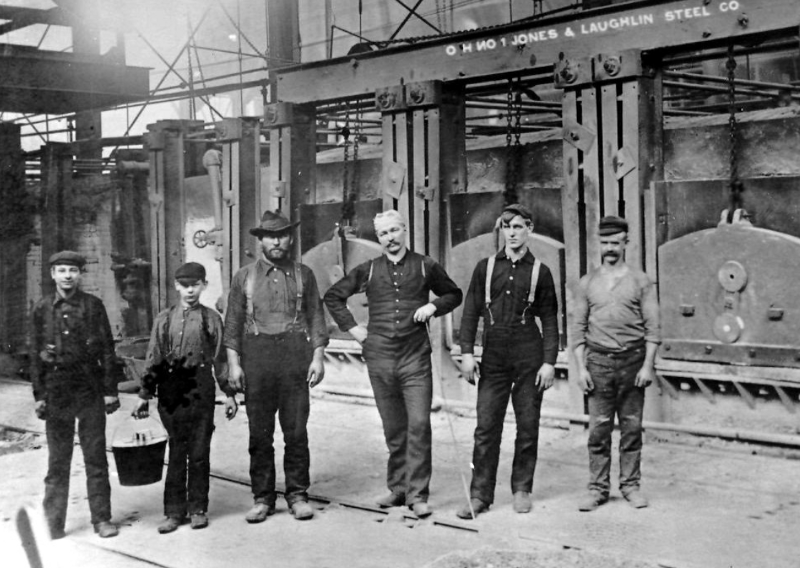

I was going to college to make sure I didn’t have to answer a question like that. It made me think of my father and grandfather who worked as laborers in a steel mill for 40 years.

“Just remember that you’re going back to college in a few weeks, and we’ll all still be here making these parts.”

There were several reasons why I attacked that morning shift like a maniac.

First, it was challenging. I’m a competitive person, and when I heard 800 parts, I immediately saw it as a goal to beat. To add to that, the other office “temps” were talking smack, and no one wanted to be the least productive out of our makeshift white collar gang.

Second, I wanted to prove a point. During two months of scheming any way to make more parts in one shift, I had a feeling that I was working on the wrong solution. The real answer lay in a more productive workforce.

In other words, our company’s productivity issue had more to do with hustle than design.

Well, I proved my theory for one morning, but my mindset changed after that short conversation with my older friend.

Would I be able to keep up that pace for an entire career? Would I be able to keep up that pace at the age of 50 versus 20?

What if the company negotiated my pace for all of those workers as the new regular quota?

How many consecutive days would they be able to grind through at a pace that had them soaked with sweat?

How many work-related injuries would show up with the front line working at that break-neck pace?

That summer experience offered two different perspectives. I came to understand the frustrations that management and labor feel with each other.

More than anything, I learned to take the time to understand the perspective of those I work with. My friend did me a great favor that day. Before that, I took an “us versus them” approach to problem-solving, and this taught me to listen to everyone when solving problems in business.

It wasn’t fair for me to prove a point with how much productivity could be squeezed out with only a few days sample size, in a job I had no intention of doing as a career.

Do I believe the laborers could have done more per shift?

Of course.

Should that quota have been what I could do once in one shift?

Of course not.

Leaders in business need to think about sustainability when setting production standards. It is not about what one can do in one day.

It is about what one can do consistently month in and month out.