My first promotion was announced in an emailed organization announcement. In an instant, I had to pivot from peer to boss.

I was 25 years old and had no idea what I was doing. Once that email was sent, 12 people reported to me.

There was no manual to tell me how I should spend my first days, weeks, and months. It was just an announcement and my growing sense of dread that I was in over my head.

I quickly learned that each person reacted to the news differently. In turn, I had to manage each of my former peers differently.

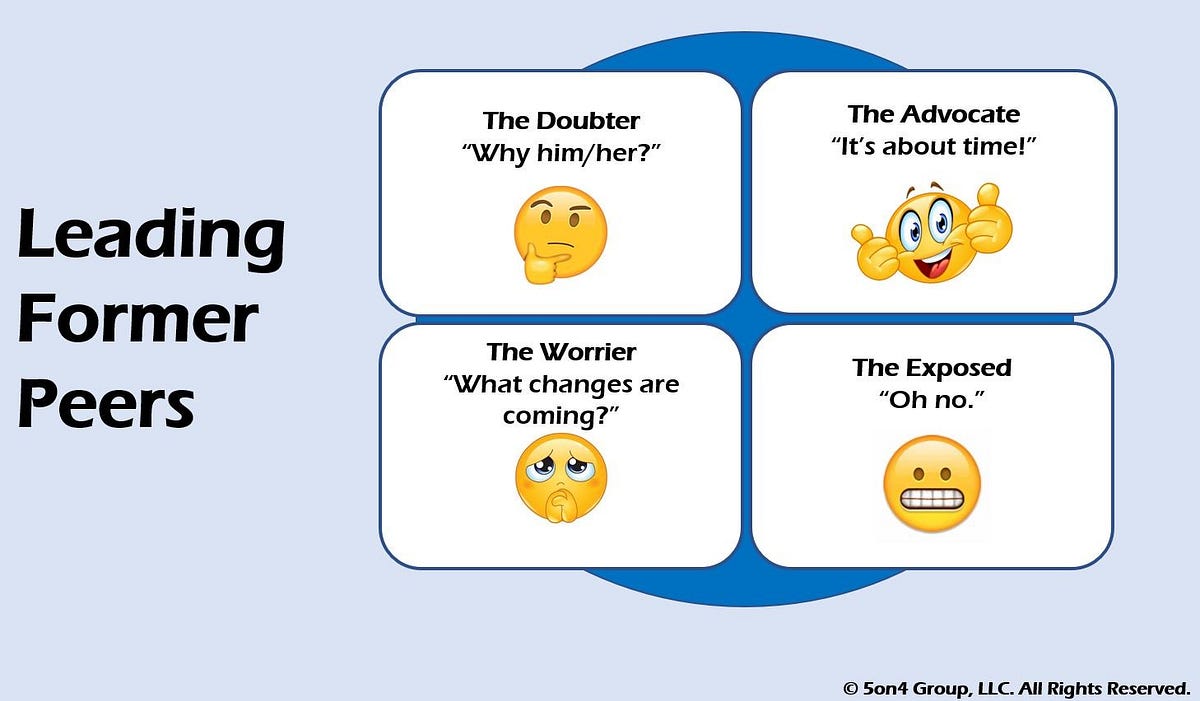

In my experience, new teams can be split into four types of people (with some exceptions).

The Advocate

The first person to congratulate me was the only person on the team younger than me. He graduated two years after me, and I spent the previous year mentoring him in his role.

He was fired up.

His mentor was now the boss, and we had an established personal relationship. He knew that I had a vested interest in his career and now I had the authority to help him.

He was my Advocate.

This young guy understood that I was keenly aware of his obstacles, having worked in the same territory. I was likely to attack those obstacles, making life easier for him.

My promotion meant that the company was willing to take chances on a young person without previous management experience. It gave him hope that his hard work would be rewarded if he performed.

As a new manager, you frequently find yourself talking to your Advocates in the early days of your new role. They give you a pulse of how the team is receiving your new direction. The Advocate is the easiest of your former peers to manage.

They are comfortable with you personally and more likely to tell you the truth. You might find yourself calling your Advocates after hours to talk through ideas.

The mistake you can make with an Advocate is letting them get so comfortable that they take advantage of you. Don’t lose sight of the differences in your roles.

You will have to make tough decisions in the best interest of the company. And those decisions might not always be in the best short-term interest of your team. Many new managers struggle to transition from peer to leader with this particular individual.

It is best to have this conversation early with your Advocate.

“Look, you know I am your biggest supporter, and that will not change. Understand that I have an entire team to lead, and they can’t see that I’m treating you any differently. Our relationship might change somehow, and I’m sure to make some decisions you won’t like. I will always give you a voice, but once I make a decision, I am counting on your support.”

In no uncertain terms, the Advocate must understand the new dynamic in your relationship. You must be their leader first and buddy second.

The Doubter

The second person to approach me was someone I considered an adversary before my promotion. From the day I started in the office, we saw each other as competition.

He was our top sales rep and had zero interest in helping me overtake him. On the contrary, he lobbied our manager not to hire me in the first place. He didn’t think the office needed another sales rep.

Why would he? He was receiving 100% of the credit for every deal, whether he worked it or not.

No matter what new account I called on, he would contrive a story about how it was already his customer. I had to ask every new customer if they knew of him, knowing he would pull this game on me.

He shook my hand, congratulated me, and offered a rehearsed line.

“I want you to know you have my full support.”

If someone says that to you, they are likely full of crap. A real supporter does it with action.

The truth is, he wanted anyone in that role except me. He didn’t think I was qualified to lead him. My former enemy saw me as a threat, and he was already calculating how he might get me out of the role.

He was my Doubter.

The Doubter believes they were the better candidate for your new job. They may have interviewed against you for the position. Even if they didn’t want your role, they believe someone else on the team would be much better suited to lead them.

That person would be anyone who might leave them alone or someone that they could control easily. It is always tricky to work with a former enemy at work.

The Doubter is good at what they do, which is why they question your authority. They might have been a favorite of your predecessor, largely because they delivered results.

What did I do as a new manager? I ignored my suspicion that he would sabotage me every chance he got. I hoped he would adjust in time and didn’t confront the uncomfortable truth about our relationship.

Worse, I was overly concerned with winning him over. I asked his opinion on everything, which emboldened him to complain more and more.

First, it was public complaining. Then, I started to hear from his peers that he was spreading discord behind my back.

It dragged the team’s morale in the mud for months before I confronted him about it. I was the manager, but I gave all of my power away to someone who was passed over for good reasons.

If you know of someone who fits The Doubter profile, address it immediately.

“I recognize my promotion might be difficult for you. You probably would not have chosen me if it was your decision.”

Tell The Doubter the things you value in them. Don’t lie. Find the things they are good at. With my Doubter, I valued his technical ability to close large deals. While the rest of the team kept trying the same old things, he creatively broke into new industries.

I was right to share that I appreciated different viewpoints and wanted him to share his ideas with me. But I also should have confronted him about his behaviors that irritated me.

“I want us to have open communication, and I promise to listen to your ideas. But you need to understand that we won’t agree on everything and I am going to make decisions you don’t like. When I do, I need your support.”

Proceed to surface your perception of his behavior.

“These are some behaviors of yours that drove me nuts as your peer. I expect to see you make changes in these areas. Is that fair?”

I was too inexperienced to implement this direct approach, and I paid for it. I handled Doubters differently in every management position thereafter.

Doubters can become Advocates but not without candid dialogue.

The Exposed

The next calls I took were from the team’s worst performers. They were nervous and had good reason to feel this way.

The Exposed are struggling to get results and know it is not a secret. You were their peer for an extended period of time and probably knew the reasons better than your predecessor. Their performance issues could be related to any number of issues.

- They work hard but are not cut out for this specific role.

- Their personal life takes up too much of their working day.

- Their previous manager was a friend and let them get away with not performing.

- They screw around on social media half the day.

- They complain about everything and drag down the office with their attitude.

You will know their flaws better than their manager did. Their guard was down around you as a peer, and you saw every blemish they guarded from management.

In my case, both individuals were hard workers. I knew them well because I ran a pilot program where we helped our struggling sales reps with prospecting.

Even with a small team doing the cold calling for them, they still didn’t have the closing skills to make the most of it. They were stuck in the same rut and unwilling to get out of their comfort zone.

I mistakenly spent most of my time with this group. I vowed to fix their problems and ended up doing all of their work while neglecting the best people on my team.

Regardless of the work I put in, they always slipped back. Ultimately, we replaced one and found a different position for the other. It took me too long and they left a long trail of problems behind.

With the Exposed group, it is best to surface the elephant in the room early. Address their performance and ask them why they think it has been a problem. If they are unwilling to share the real reasons, offer your perspective.

Next, ask for their plan to change. It is important that they create the plan and not you. As their manager, you will offer insight but they need to own the plan and believe in it.

Your role is to help this person improve without doing the heavy lifting for them.

The Worrier

Some people didn’t call me at all. They were so worried about the change that they ignored it.

The Worriers make up the largest contingent of any team a new manager inherits. Whether they are performing or not, a new manager gives them anxiety. You represent change, and change is frightening to The Worrier.

Worriers envision all of the crazy things you are going to do as a manager. They fret that you won’t like them and agonize about what your promotion means to their future.

Most of it is manufactured in their heads but they will worry anyway.

The Worriers were polite on the phone and gave me no reason to think they were worrying. It was only months later that they told me about their initial fears.

One person thought I would replace him because there were no steel mills in his territory and he knew steel mills were my biggest customers. Given that he beat me in sales the prior year, this fear seemed odd.

Another was worried that I would take away his ability to work from home. He worried about this even though I worked from a home office.

As a manager, draw out the fears of a worrier immediately. People share information in layers, like peeling an onion.

A new manager needs to ask questions that draw out concerns and follow up with several open-ended probes.

- What are you afraid that I might change?

- What do you want me to change?

- If you were me, what would you change?

- What concerns you about me in this role?

- What do you want to know about the type of manager I plan to be?

Teams take their cues and adapt their behaviors based on how their manager behaves. If you ask questions, they will return the favor and be comfortable raising their hand.

There is a little bit of the Worrier in all of us. Let your team voice their concerns, no matter how implausible they might be.

Tailor Your Approach

Thinking about your team in these four buckets helps you focus on their motivation and fears, which are the driving forces behind performance in any company.

If there is one theme that runs through the approaches I outlined, it is candor. It serves no one when you keep your opinions to yourself. Share your immediate thoughts and make it safe for your team to reciprocate.

In management, there is no “one size fits all” approach. Tailor your style with each person and accelerate how quickly you get results.

Are you interested in similar content on leadership, management, and careers? Receive articles and updates like this directly to your email.

We value your privacy and will never spam you.