“Clack, clack, clack.”

In boxing, the sound of two pieces of wood smacking together signals ten seconds remaining in the round.

To Muhammad Ali, the warning was his cue to make an impression with the judges.

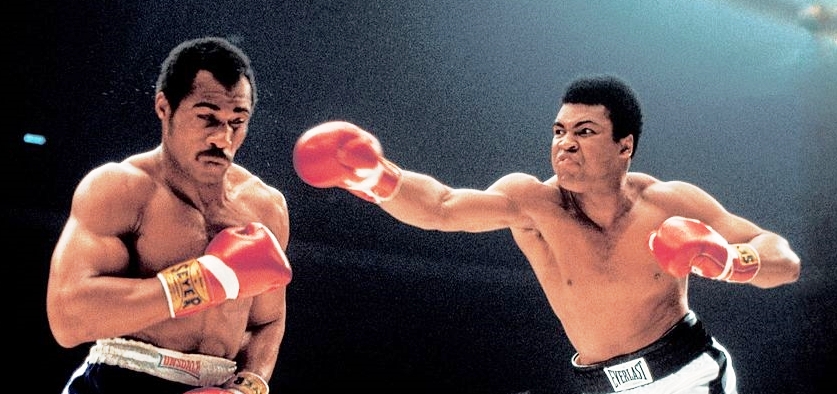

All three of Ali’s fights with Ken Norton ended in decisions.

Muhammad Ali connects with a right cross against Ken Norton.

After he lost the first fight by decision, a fight in which Norton broke his jaw, Ali was determined to win over the judges in subsequent rematches.

Very often, in close rounds, [Muhammad] Ali would flurry at the end so that the impression he left in the judges’ minds was that he won the round. Obviously, rounds should be scored for the full three minutes but there is no question that humans being human will give more credit for the last part of the round.”

Bob Arum, boxing promoter

Ali would win his second and third fights with Norton by unanimous decision, partly by finishing strong in each round.

Years later, “Sugar” Ray Leonard would use the same tactic against the heavily favored “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler. Returning to the ring after a three-year retirement, Leonard knew better than to rumble with the more powerful Hagler.

Leonard’s strategy was to win the final 30 seconds of every round after making the rest of each round as uneventful as possible. For most of the round, Leonard would dance around his dangerous opponent, never engaging for too long.

With 30 seconds remaining, “Sugar” Ray would engage in an exaggerated flourish, showing off his hand speed and signature showboating. Most of these punches didn’t land and those that did connect were not enough to hurt Hagler.

"Sugar" Ray Leonard (left) battles "Marvelous" Marvin Hagler in 1987.

It didn’t matter.

Leonard “stole” enough rounds to finish with the unanimous decision, doing just enough to convince two judges that he won the fight.

Recency Bias At Work

Recency bias is our human tendency to remember the most recently presented information best.

“Top 10” lists make their way around the internet at the end of every year and they are typically skewed toward recent events. When an event does make the list from early in the year, we can scarcely recall it happening.

Managers face the same challenge with short-term memory. When it comes to your pay increase, managers must justify your raise versus your peers.

A typical pool of money for increases might represent 3% of the payroll. In most companies, and certainly large organizations, annual pay increases are treated as a “zero-sum game.”

If your manager decides to give you a raise well above 3%, one or more people will come in below the average.

To decide on percentages, managers rely on your objective results from the past year. How were you measured? How did you finish versus target and versus your peers?

But, what if two people had comparable annual results that were skewed differently throughout the year? Take an example of two sales managers who finished with identical results.

The first had an incredible spring and summer but fell off dramatically toward the end of the year. The second manager started slowly and caught fire in the fourth quarter, making up a big gap and surprising their manager to the upside.

With identical results, who will receive the best pay increase?

I can unapologetically state that as a manager, I am rewarding the individual with recent success.

One year is a subjective measurement period. In business, twelve months can feel like an eternity. If someone's performance is noticeably declining, you risk sending an apathetic message if you reward for the entire year.

Markets change, companies change, new employees are hired and raise the bar. If someone is not keeping pace with the rate of change, their pay should reflect the reality of their contributions.

You Still Have Time

With last year in the books, you might assume that your pay raise is a foregone conclusion. You might be wrong.

Most managers are overwhelmed with business in December and spend most of January catching up. February is a month where most companies set deadlines for completing annual appraisals and making pay decisions.

Managers are people and procrastinate just like you. It is likely that your manager will spend their last weekend in February writing 15 performance reviews using only their memory. What information about you will be easily recovered?

You have 30 seconds left in the round, so make it count.

- Step up communication with your manager. Like most people, you were buried with work ending the year. When you did talk with your boss, it was tactical and involved putting out a fire. Take this opportunity to re-engage with your manager on the progress you’ve made in the last three months. Pull your manager out of the weeds and help them see what you’ve built in your area of responsibility. Start helping your manager write your annual appraisal.

- Don’t fall into the same recency trap when you write your self-appraisal. Just as your manager will fail to remember many of your good deeds from the first half of the year, you will struggle to recall them as well. Knowing that your manager will recall recent victories, make sure that your self-appraisal highlights all of the great things you did early in the year. Help your manager recall a full picture of your great year.

- It’s not too late to engage with your manager’s hot buttons. Every manager is pushing an initiative or two. Most find it frustratingly slow to convince their team to join in on a change effort. You might be part of the problem, especially if you were busy at the end of the year. Change that narrative and plug yourself in on your manager’s crusade. Engage during meetings, demonstrate actions that show that you are onboard. Deliver tangible results that your boss can trumpet as proof that the initiative is working.

If all of this feels like gamesmanship to you, I get it. I like my work to speak for itself and so did “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler.

With perspective and Leonard's confession that he “gamed” the judges, many historians have re-scored the fight with Hagler as the clear winner. Hagler didn’t need perspective as he declared himself the rightful winner before he left the ring that day.

It's unfair man, it's unfair.

"Marvelous" Marvin Hagler

Recency bias worked against Hagler, while Leonard used it in his favor.

When it comes to your next pay raise, you can let this cognitive effect hurt your odds or you can take control and use it in your favor.

Are you tired of reading the same regurgitated management advice?

Do you want to learn from someone who has done more than read books about leadership? Enter your email below and subscribe to my newsletter.

We value your privacy and will never spam you.