“Don’t you think it would be easier to ask the people doing the work?”

This question came from a union worker at an Indiana steel mill. He was thoroughly unimpressed with my plan to optimize his factory, nor did he think his plant manager could lead a team through a crisis.

I worked for GE in 2000. Six Sigma was our secret weapon. Though Motorola introduced this process improvement methodology, Jack Welch made it famous. Jack made Six Sigma one of his signature initiatives, touting the cost-saving magic that helped GE beat earnings estimates like a drum.

Six Sigma was so closely tied to GE that we sold it to our biggest customers. For a fixed fee, we would attack your inefficient process with data. The process was defined by five words: Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. With data, we could help an executive lead a team through a crisis.

Most every employee at GE was trained on Six Sigma in some fashion. We had a belt system like in martial arts. Getting a green belt was like earning a trophy in youth soccer, you just had to participate.

I karate-chopped my way through classes, leaving the GE dojo to take on my black belt project. Once obtained, GE could bill me out nearly as high as our most senior electrical engineers. This was nuts, of course.

Putting Theory To The Test

I was just a kid and my knowledge was classroom-based. That didn’t stop GE from selling a quality study to one of the largest steel companies in the world for a fixed price.

This particular company had a serious problem in their cold mill, which is a major driver of any mill’s profits. Throughput was down in this location, lagging all of their sister plants. The plant manager had engineers studying reports around the clock with no line of sight to a solution.

This plant manager was desperate for ideas while leading through this crisis. Demand was high for cold-rolled steel and he couldn’t keep his mill running. His career was at stake, so he turned to GE to consult on the problem.

It must have been the Jack Welch halo. When I showed up in Banana Republic chinos and a laptop, he didn’t kick me out. I spent the summer collecting and analyzing data on process points.

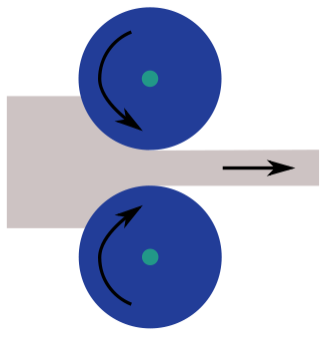

Finishing steel is done by pulling a coil of steel through large rollers which continuously narrow the gauge. Think about rolling dough for a pizza but instead using massive rolling pins and coils of steel. Incredibly powerful motors drive these rolls as the coil is reduced further at each stand.

The coil needs to be fed into the first two rolling pins. This is done by an operator with the title of “feeder,” who works in a small shack with a view of the line. The feeder lined up the coil manually, pulling it through with various controls.

The plant manager asked me to start with his engineering team’s assumptions. That group spent months in a draft room, guessing at the potential problems. Their solutions were complex, technical and most were expensive.

Complex Solutions Are Not Always Better

The best place to collect data was in the feeder shanty. I strolled up on my first day looking like I just came from the Catalina wine mixer. Well, aside from the hard helmet, goggles, earplugs and plastic toe caps they handed me at the maintenance shed.

I opened the door to the shanty, excited to meet my new office mate. He peeked over his shoulder while still running the line and greeted me warmly with, “Who the f@$k are you?”

My old man was a steelworker and so was my grandfather. I was no stranger to friendly greetings such as this. I smiled and told him what I would be doing over the coming months.

He looked at me with disdain, “Don’t you think it would be easier to ask the people doing the work?” I conveyed that I absolutely wanted his feedback and was prepared to leave no stone unturned.

The operator thought I was wasting time, “I’ve been working in this shanty for 20 years. We need to fix our fluid system and we’ll start hitting quotas again.”

This struck me as an over-simplistic take on a complex problem. In what must have been an overtly condescending tone, I responded with, “I promise you that we’ll be thorough in this investigation. I’ve recorded your concern in my notes.”

I couldn’t imagine how a large, publicly-traded company would spend top dollar to fix a problem with a solution this simple. The operator kept going, “This mill gets stuck multiple times every shift. Every time that happens, it takes 5–10 minutes to pull the coil back out and start over. I need the lubricant system working or it will keep happening.”

This solution was nowhere in the 50-page analysis from the plant’s engineering team. They wanted me to look at motor performance, variable frequency drives, control systems and a host of other technical areas.

I promised the operator that his idea would be heard. He shrugged, tugged on his cigarette and offered some advice, “If you’re going to work in the mill, get some steel-toed boots.” That night, I bought some Red Wing boots and wore jeans for the rest of the summer.

I spent three months collecting thousands of data points on every aspect of the mill. We controlled for every concerning item in the engineering report, running ever more complicated statistical analyses.

We swapped out a large motor for a spare and studied throughput for a week. We performed maintenance on the analog drive system, then studied the data again. We changed out lubricants, tweaked roll speeds, motor torque, etc.

The data told us nothing. Soon, I would present my findings and I had nothing. Three months. $250,000.

Nothing.

Walk A Mile In Their Shoes

I got to know this operator well over three months. We shared this tiny shack that was clearly built with a maximum capacity of one. He did his job while I tapped away on my laptop, both of us sweating in a sweltering steel mill.

Forced to talk with each other, we found that we had plenty in common. He had family in Michigan, near where I grew up. We both played football in high school. He rooted for the Chicago Cubs and I routinely stumbled out of Wrigley Field on weekends.

He hated working for this company. Management and engineering had no interest in his opinion. They gave him orders and blamed him when quotas weren’t met. They had no clue on how to lead a team through a crisis.

He felt like he had all of the accountability and zero input into how to get there.

The union wasn’t exactly winning friends and influencing people either. Workers made life miserable on engineers when they needed to take a measurement or gather information.

I saw firsthand how engineers were talked about. The environment was uncomfortable, bordering on toxic. The two sides just quit talking, leaving the engineers in a position where they could only solve problems by studying data.

Desperate for a solution, I confided in my feeder shack buddy. He rolled his eyes and repeated his solution, “Get me a new fluid system.”

The cost was nominal in relation to the other solutions. Picture a much larger version of a car’s windshield wiper spray. The fluid was sprayed on the coil rollers just before the steel “stuck” into the first roll. Without this lubricant, the steel would jam and create a time-wasting mess.

I was told by the engineers that the operator was just whining. Something this small had nothing to do with productivity. I had my doubts. With all of the brainpower on the issue, there was no way a simple solution could be the driver. Regardless, I convinced an engineer to swap out the spray system and studied the data the following week.

In the first shift with the new fluid system, the line experienced zero stoppages. The roll didn’t stick once. The next day was seamless and over the next week, downtime dropped by 50%.

My guy’s chest was puffed out with pride all week. He was genuinely thankful that someone listened to him and made his job easier. He wasn’t interested in doing a bad job and was excited to see “his line” operating at peak potential again.

$250,000 For A $5,000 Solution

I put together a 50-page report followed by a 100-page presentation to show the findings. We eliminated every hypothesis from the engineering team through trial and error.

I was anxious to present the one finding that mattered. How could I explain that I spent three months to find one simple change that I learned about on the first day? Some “black belt” I was.

I presented to the plant manager that the only change that made a difference was a new fluid system, at a nominal cost. We eliminated all but a handful of line stoppages every hour.

On the payoff slide where I went into detail, I included a picture of the shack operator and his name. I gave him credit for the idea. Also on this slide, I added a picture of the engineer who installed the new fluid system and gave him credit for finding the correct solution.

Far from being gratuitous, I was embarrassed. I wanted to admit that improvements had nothing to do with my study and everything to do with ideas from his team.

I expected the plant manager to ask for his money back. Instead, he lauded the study. He didn’t care how the problem got solved. The mill was producing again and his stock was about to rise as an executive who could lead a team through a crisis.

Both individuals received direct praise from the plant manager in front of their peers. He praised their teamwork in a group meeting before the next shift. I was asked to follow up on a few findings from the study.

When I returned to the mill, a funny thing happened. Operators started approaching me with ideas that could drive productivity. Some had lists they kept for years. They hadn’t bothered to share because they didn’t believe they had a voice.

Morale was up and it was palpable when you walked the line. Guys were communicating more, laughing, hustling. Operators and engineers were talking through issues together. They started to act like a team.

That mill had a crisis of their own making. Today, every company is facing a crisis and the lessons from this situation apply.

1. Don’t Start With Data

In a crisis, data is not going to tell the full story. In March of 2020, the faucet turned off for most companies in the world. When you have numbers saying your sales are off 70% from the previous month, what’s the point?

Unfortunately, this is when many managers lean into metrics. Similar to a panicked stock trader seeing a bad trend, their imaginations run wild. Companies have a tendency to over-measure in tough times and paralyze their teams in a crisis.

If a movie theater catches on fire, you don’t start counting heads and holding meetings on the best way out. Time is of the essence. Be clear on where the exits are and allow people flexibility in how to get out. There will be time for a post-mortem later.

Start talking to your people more. Ask them what they are seeing and what they would like to implement. What can you take off their plate so they can focus on their job?

2. Listening Is Nice, Implementing Is Better

A senior executive once visited my office for an incredible two-hour brainstorming session. He pulled 20 of us together and led with, “What do you need from me to sell more?”

After a slow start, everyone chipped in. We filled three whiteboards with ideas. The energy was contagious. He assigned someone in the group to consolidate the ideas and share them with the group.

Our office buzzed for two weeks. In the third week, we asked our manager if he’d heard anything. Crickets. Two months later, we gave up on any of it. It would have been better if that VP never visited.

One year after that brainstorming session, the executive was out and replaced with a fresh face. He came to Chicago, pulled us all together and asked, “What can I do to help?”

This time, the meeting was over in 10 minutes. We didn’t waste time on another meeting headed for nowhere.

Yes, people want you to listen to them. But you do more damage by listening and sitting idle than not listening at all. If you don’t have the courage to act when your team makes suggestions, don’t ask.

3. Silos Start With Managers

My friend runs a large company that has been forced to make deep staffing cuts. His industry is particularly hard hit and the cuts were agonizing. Making matters worse, his CFO and President nearly came to blows. Both are trying to do their jobs during a trying time, but each has a different mandate.

From a financial perspective, decisions are black and white if the company is to survive. From an operational standpoint, the President needs to retain enough talent to maintain the company’s culture and thrive on the other side of this mess.

The CEO recognized that he was part of the problem. He shared this, “We have a meeting, emotions are high but I feel like we leave with clear direction. Within five minutes of the meeting ending, both have called me to complain about the other and negotiate a different path.”

For obvious reasons, this is unhealthy. As long as the CEO allows this behavior and lets decisions change after the meeting, there is no need to meet at all.

He changed his approach, “I ask them if they want to patch in the other person. If not, they can convene without me and let me know what they determined. As long as I act as judge and rule in favor of one or the other, I’m not helping. I need to encourage them to work together and present jointly to me as one company.”

The plant manager at the steel mill had no interest in bringing his engineers and union operators together. An effective leader would create joint teams and be as inclusive as possible when brainstorming solutions. Encourage different position groups to meet without you and ask them to present their ideas as one.

In a crisis, the last thing you need is in-fighting between departments. The overwhelming challenge should bring your team together, not tear it apart.

Lead Like A Consultant

There is an old fable about an owner calling out an engineer to fix a major problem in his auto plant. The engineer shows up, walks around the line for 15 minutes and then draws an X in chalk on the machine. The maintenance team goes to work and the line starts running.

The owner is thrilled and asks him to send an invoice. The bill arrives for $10,000 and the owner demands an itemized account. The engineer sends another invoice indicating $1 for the chalk and $9,999 for knowing where to put it.

In reality, consultants don’t work like that.

Consultants are not effective because they know where to draw an X. They win by finding that person and giving them a voice. They ask questions of everyone, management down to the front lines. They don’t arrive with answers, but they are paid to pull them from people who do.

Great managers behave in the same fashion. They solicit ideas from front-line employees and make them feel as if every initiative was created just for them. I wrote about this “IKEA Effect” as a management practice that consistently generates results.

Assume nothing, ask questions and have the courage to act on good ideas. Repeat these steps regularly and soon enough, you will lead your team through this latest crisis.

Like what you are reading? You can receive articles and updates like this directly to your email. We'll treat your information responsibly.

We value your privacy and will never spam you.